There is a constant interplay between my reading life, my writing life and what we like to call ‘the real world’. Resonances, echoes, parallels.

I first read of the atrocities committed on the Abrolhos islands, off the coast of Western Australia, back in 1980, in a book called Island of the Angry Ghosts. The Dutch ship, Batavia, along with a small fleet of 8 other ships, sailed from Amsterdam in 1629 , bound for the Spice Islands. Their specific destination was the island of Java, and the city of Batavia – what we now know as Jakarta.

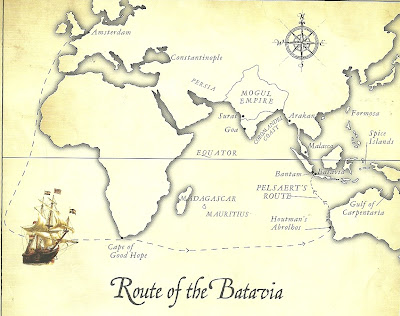

The Dutch had discovered that the most efficient way to reach the Spice Islands was to head in a south-westerly direction from Amsterdam – towards the east coast of Brazil, in South America – rather than heading directly south and following the African coast. For the going down the African coast and around the Horn was slow; ships could be becalmed for days, for weeks on end. Instead, the Dutch used the strong winds in those southern latitudes, around 40 degrees south – which were called ‘the Roaring Forties’ – to speed them across the southern Atlantic and then the southern Indian oceans.

Back in 1980 we were setting off on our own adventure – a trip around Australia. I had taken long service leave, and my then wife and I took our three children (aged 9, 7 and 3 at the time) out of school for four months to make the trip. I half planned to write a book about the journey. [My concept – which still seems to me a good idea – was to write a sort of resource book to help parents ‘home teach’ their children as they travelled around the continent – an activity that was quite common back then. As a result, I’d started reading books like Storm Boy, Colin Thiele’s account of a boy and his love for pelicans as he grew up in the Coorong region of South Australia. Parents could read Storm Boy to their children as they explored the Coorong on their long trek around Australia; the experience of the ‘place’ would be deepened and enlivened by reading this piece of literature, and the experience of the literature would be enhanced too. That was my aspiration.] It was this book-concept that led me to read Hugh Edwards’ account, Island of the Angry Ghosts.

So, back to the Batavia: the idea was – you caught the Roaring Forties, and raced along the 40th parallel at a cracking pace (of about 8 knots an hour), then – when the time seemed right – you did a left turn and headed northward to The Spice Islands. Even though boats following this route travelled further, they took something like six months less time to reach their goal. The route, however, did have its problems. The Dutch had already chartered some of the coast of Western Australia, and had maps that indicated that there were dangerous reefs along the coast of Het Zuidland – as the Dutch called the huge land mass that we call Australia. One particularly dangerous groups of reefs and islands were Houtman’s Abrolhos Islands; ships had run aground there before. The captain of the Batavia knew full well how dangerous the Abrolhos Islands were.

The Batavia was laden with gold and jewels worth an enormous amount of money. Francisco Pelsaert was the commander of the fleet, and was aboard the Batavia. He had been placed in charge by the Dutch East India Company (DEIC). The captain of the Batavia, Jacobsz, had begun to conspire with Jeronimus, another high official in the DEIC, to kill Pelseart, take over command, and steal all the gold. But Jacobsz made a serious error of judgement, and before the mutiny could be carried out, the ship ran aground and began to break up on the reefs of the Abrolhos. Around 250 people – sailors, soldiers, families going to settle in Batavia – were aboard the ship.

The Abrolhos Islands are desolate, windswept, and have no permanent supply of water. Jacobsz and Pelseart, along with 46 others set off in the longboat in search of water on the mainland. Finding none, they decided to set out for Batavia – over 1000 kilometres to the north - leaving the other survivors to fend as best they could.

While they were gone - for a period of over eight weeks - Jeronimus and his fellow mutineers systematically murdered dozens of their fellow survivors, in an horrendous reign of terror. A brief account like this cannot begin to capture the brutality and viciousness of Jeronimus and his followers.

One incident will suffice to give some sense of just how bad things were. Some five or six weeks into the ordeal, Jeronimus invited the pastor and his wife to dinner in his tent. The pastor thought this would be an opportunity to persuade Jeronimus to be more ‘humane’. Jeronimus welcomed the pastor and his wife, fed them well, offered them wine, and was a charming and amenable host. And while he entertained these two trusting, religious people, his thugs went to the pastor’s tent and slaughtered all six of his children, and threw them into a pit.

Of the 250 people on the Batavia, over 100 were murdered. The more attractive women were kept as sex-slaves; the older and less attractive women were murdered. Any men who showed dissent, or even independence, were killed. Only men who swore allegiance to Jeronimus, and who were able to work, were kept alive. Babies were poisoned, drowned, beheaded, or had their throats slit – Jeronimus could not stand their whimpering and so ordered their deaths; after all, what good were they? They did no useful work.

Fitzsimons’ book is almost 500 pages long. It seems to have been well researched, and Fitzsimons is dab hand at telling a good yarn. And this is a great yarn. As the cover says: ‘Betrayal. Shipwreck. Murder. Sexual slavery. Courage. A Spine-Chilling Chapter in Australian History.’ It’s one of those books you can’t put down; and the more you read, the more drawn into the story you become.

The initial real world resonance of this tale was with Auschwitz and the gas chambers of Nazi Germany. I recalled Tom Keneally’s book - Schindler’s Ark – and Spielberg’s film, Schindler’s List: there was about Jeronimus the same sociopathic disregard for other human beings. George Steiner once wrote about how one of the Concentration Camp Commandants would spend his evenings conducting dinner parties, where he would be charming company, and before going to bed would listen to classical music – some of the most beautiful music ever created. Then, in the morning, he would oversee the mass extermination of Jewish men and women and children. And Steiner asked, ‘How was this possible? How could the one man both listen to classical music and murder innocent people?’

One of the most striking things about Fitzsimon’s book is his recreation of Jeronimus. He was a man who people looked up to, were attracted to; he was – it seems – always plausible. How else could he have so deceived the pastor in such a cruel fashion.

The other real world resonance was with the horrific killings at Port Arthur in the 1990s, when the lone gunman – another sociopaths – shot dozens of people, and killed 35: Australia’s worst mass killing, in recent times, at least, although falling well short of the numbers of indigenous Australians who were massacred in the 1800s and the early 1900s by pastoralists.

The literary resonance was with ‘Lord of the Flies’. There are many parallels. Jeronimus was very much like Golding’s character Jack. Those who have read the novel (or seen the film) will recall Jack who had many of the qualities of a leader, but who was consumed by sociopathic emotions. Jack exerted his power by a simple process of ‘divide and conquer’, breaking Ralph’s leadership by creating a tribe of his own, and picking off his enemies one by one – Simon, Piggy ...

Perhaps the greatest hero of the Batavia was Willie Hayes, a man similar to Ralph in many ways. He was solid, a man of common sense and decency. His systematic leadership enabled the 50 people on the ‘Large island’ two survive and - though it’s a relative term – ‘prosper’.

Jeronimus’s strategy had been to sent Hayes with the other soldiers to reduce their influence. He also expected them to die there; he believed there was no water on the island. (As it turned out, there was an ample water supply.)

The ending of the Batavia story also has echoes of Golding’s book. Just as Ralph is saved at the last minute by the timely arrival of a boat and adult naval officers, so Hayes and his men were saved by Pelsaert’s return, just as Jeronimus and his thugs were about to storm the island.

Having woken early on a particular Saturday morning, I finished reading Batavia the last forty or so pages of the book. Thoughts of Jack and ‘Lord of the Flies’ and of and Jeronimus and the Batavia and the massacre of a hundred or more souls by this soul-less man were awash in my mind. I turned on the television for the morning news to hear of the massacre of almost one hundred young people on another island.

Donne wrote – ‘Do not send to ask for whom the bell tolls – it tolls for thee’. I’d just spent three days at a school Music Camp, and couldn’t help thinking: ‘What if some sociopathic ideologue, convinced that God had spoken directly to him and told him how he could right the world, had walked into the camp and shot children and teachers at will?’

Andrew Bolt’s immediate reaction was to write in his blog that the murders in Norway were the work of a Muslim terrorist. One can only hope that his discovery that the Norwegian was in fact a Fundamentalist Christian (!) might have caused Bolt to at least falter – for a step or two – in his blind march towards his own ‘truth’ – that the Christians are the good guys, the bad guys are the Muslims!

I’m increasingly convinced that the people we have most to fear are those who are utterly convinced that GOD is on their side. People like this Norwegian maniac. And the suicide bombers who daily trade their life on this earth for their rewards in heaven, and take out two or six or a dozen or more people with them.

For the tolling bell rings with at least two distinct tones. One is the tone that Donne recognised: no man is an island, complete unto himself, and the bell that tolls for the death of another is a reminder that that same bell will toll for us one day.

At the start of this year I showed my year 12 students the opening 20 minutes of Dead Poets Society. The new English teacher John Keating (played by Robin Williams) takes his class into the foyer of the school, where the photographs of the school’s ‘old boys’ are on display. He had Pitt, one of the boys, read a poem by the 16th writer Robert Herrick:

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may

For summer is a-flying

And that sweet rose that blooms today

Tomorrow will be dying.

Pointing to the photographs, he tells his class that those ‘old boys’ were once like them, full of hormones, full of dreams and aspirations. But now, he says, they are ‘food for worms’. Because each of us will, one day, stop breathing, grow cold and die. We are all ‘food for worms’; which is why we must ‘gather rosebuds ... while we may’ – we must ‘seize the day’ and ‘make our lives extraordinary’.

But Donne’s bell rings with another tone too. It is the sombre note that underlies what Golding had to tell us in Lord of the Flies: that every one of us, every single one of us, has deep within us the capacity to murder, or to collude in murder – to turn our eyes away and pretend that it is none of our business. When Simon stumbles into the tribe’s wild incantation – “Kill the pig. Cut his throat. Spill his blood.” – there are almost no innocent by-standers. Not even Ralph. The tribe kills Simon, and Piggy and Ralph kick and scratch and tear just like the others. The other survivors on the island that came to be called Batavia’s Graveyard – and there was over one hundred of them – heard the screams in the night, but out of fear for themselves they did nothing. The townsfolk who lived in villages nearby Auschwitz and Belsen and the rest saw the smoke, could smell that human death was occurring, but turned their heads away, and said, in effect, ‘It has nothing to do with me’. John Howard knew that during his time in the parliament of Australia, Australian governments had persisted with a policy that involved taking indigenous children from their biological parents, but he still refused to say ‘Sorry’ to indigenous people because – he claimed- the dispossession of black people in Australia happened long ago. Just as the Labor government took no action when Indonesian troops massacred East Timorese rebels. Just are we allow children to be held in a concentration camp in one of Australia’s most inhospitable regions – Woomera. I think that one of the reasons that Howard does attract such bitterness is because – like Jeronimus, like Jack, like the Holocaust-deniers, like the Norwegian killer – he claims to be speaking while wearing the cloak of truth. When the ‘children overboard’ incident occurred – it was claimed that refugees who were passing their children over the side of a sinking boat to family members already in the water were actually ‘throwing their children overboard’ – John Howard not only insisted that this was so, that these were so inhumane that they were throwing their children overboard, and we don’t want people who would behave like that in OUR country – he continued to insist it was so even after he had been told by naval authorities that it was not true. And why – because he had been behind in the polls, and the polling was turning more and more his way every time he told that story!

The Catholic Church calls it ‘original sin’ – the darkness in the human soul, the capacity to commit atrocities or to condone atrocities, or to turn a blind eye to atrocities. We are, none of us, ‘an island unto himself’; we are all part of the promontory, we are all ‘tarred with the same brush’. Our common humanity, our common inhumanity.

In The Essential Gesture, a collection of essays, the South African writer Nadine Gordimer writes:

All that a writer can do, as a writer, is to go on writing the truth as he sees it ... his ‘private view’ of events , whether they be great public ones of wars and revolution or the individual and intimate ones of daily personal life.

Gordimer’s essays date from the Aparthied days in South Africa. She quotes Nietzsche: ‘Great problems are in the streets.’ She describes the reactions of her own tribe – white South Africans – at that time:

.. the gap between the committed and the indifferent is a Sahara ... Kindly and decent, within the strict limits of their ‘own kind’ (white, good Christians, good Jews, members of the country clubs....), the indifferent do not want to extend the limit by so much as one human pulse. Where the pretty suburban garden ends, the desert begins.

And when anything happens that might cause them ‘discomfort’, cause them to wonder whether ... could it possibly be that ... we are perhaps ... wrong ... the subject is dropped into the dark cupboard of questions that are not to be dealt with.

Now and then, I fall out of the habit of writing. After all, who reads this stuff anyway. Anybody? And if they do read it, what difference does it make?

But for me writing is, as Gordimer calls it, ‘the essential gesture’. It’s the one activity where I am not hiding behind charm or deceit or a mask or a laugh or a story or silence or kind words. It’s where I try to present and confront the truth as I see it. There is always the danger that this 'grappling to speak the truth' might be just another form of self-deceit, itself a kind of mask. And even if is an honest, unsullied gesture towards truth, it can never be any more than a partial truth, a temporary truth, a draft version of an outline of what I think. Like a potter with his clay on the wheel, the object – what I believe, what I think, what is truth - takes shape as I work on it. What sounds like truth at the time. Each sentence comes closer, or drifts further away, from a truthful statement. The pot I am throwing, the shape of the pot I am throwing, emerges as I work, and I know the enterprise can all too easily collapse – the pot’s shape can just fall way, and it becomes ugly, misshapen, not at all what it should be...

But it’s working on it that is the essential gesture.

No comments:

Post a Comment